Young museum worker breathes new life into ancient bamboo, wooden slips

During the summer vacation period, the Jingzhou Museum in Jingzhou—a national historical and cultural city in central China's Hubei Province—has witnessed a surge of visitors.

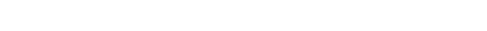

Inside the exhibition hall themed on bamboo and wooden slips unearthed in Jingzhou, museum worker and exhibition organizer Jiang Lujing guides tourists through the fascinating stories behind these ancient slips.

Photo shows bamboo slips unearthed from the Wangjiazui cemetery of the Chu state during the Warring States Period (475 BC–221 BC) in Jingzhou, central China's Hubei Province. (Photo/Shi Shaohua)

Bamboo and wooden slips served as the primary medium for recording and transmitting written information in ancient China, spanning from the Shang Dynasty (1600 BC-1046 BC) through the Wei and Jin dynasties (220–420). The academic study of these artifacts represents a highly specialized field with limited public appeal, making it a typical example of an obscure but essential research area.

After graduating with a master's degree in historical documentation from Jilin University in 2012, Jiang joined the staff of the Jingzhou Museum. Over the past decade, he has participated in the excavation and cataloging of several collections of bamboo and wooden slips from the Chu state during the Warring States Period (475 BC–221 BC) and the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), while continuously advancing research and exhibition efforts.

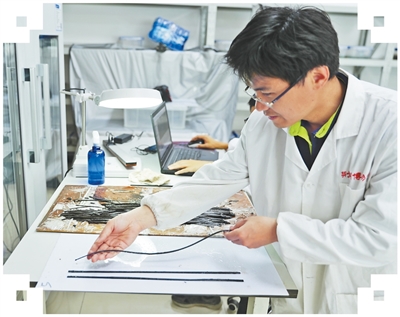

In 2019, Jiang and his colleagues took part in the excavation of bamboo slips from a tomb on the north bank of the Longhui River in Jingzhou.

The excavation, protection, and restoration of bamboo and wooden slips represent a race against time.

"Freshly unearthed bamboo slips are as soft as noodles and extremely fragile. Once exposed to air, they oxidize rapidly and turn black, potentially causing the written characters to disappear instantly," Jiang said.

The careful removal of individual slips requires meticulous attention to detail, involving soil cleaning, drawing, taking photos, and systematic numbering.

"When unearthed, the bamboo slips have been compressed into irregular, hardened masses. We must extract them one by one from top to bottom, assigning each slip a number to preserve as much original information as possible," Jiang said.

Photo shows bamboo slips unearthed from a tomb of the Chu state during the Warring States Period (475 BC–221 BC). (Photo/Chen Xinping)

Through processes including extraction, surface cleaning, infrared scanning, and dehydration treatment, the originally blurred characters on the bamboo slips gradually become legible.

As the site of the ancient Chu capital, Jingzhou has yielded abundant bamboo slips with rich content. To date, over 5,000 slips from the Chu state and nearly 10,000 slips from the Qin (221 BC–207 BC) and Han dynasties have been excavated from more than 20 tombs and one ancient well in the city.

"Each batch of unearthed slips represents the rescue of a segment of civilization buried underground," Jiang said.

Following data collection, the painstaking work of analysis begins. Jiang spends most of his working hours studying infrared-scanned images of bamboo slips on the computer, deciphering ancient characters.

The Chu state employed a writing system that belonged to ancient characters during the Warring States Period. Among the materials Jiang currently studies are bamboo slips unearthed from the Wangjiazui cemetery in Jingzhou in 2021, containing versions of "The Book of Songs," the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, dating back more than 2,000 years, that circulated in the Chu state.

"The version of 'The Book of Songs' we see today has largely undergone editorial processing," Jiang said, adding that archaeological discoveries of bamboo slips from the Chu state provide crucial evidence for understanding the original appearance of pre-Qin classical texts.

In recent years, Jiang and his colleagues have conducted extensive research and verification, providing important supplementary materials to traditional written records.

Jiang Lujing cleans bamboo slips from a tomb of the Chu state during the Warring States Period (475 BC–221 BC) on the bank of the Longhui River in Jingzhou, central China's Hubei Province. (Photo/Shi Shaohua)

Due to factors including their great antiquity, blurred characters, obscure content, and high interpretive threshold, the academic study of bamboo and wooden slips still faces significant challenges.

The Jingzhou Museum brings together three generations of researchers engaged in the cataloging and study of bamboo and wooden slips. Born in the 1980s, Jiang has gradually emerged as a backbone in the field. He constantly considers how to make better use of research results and share archaeological findings with the public.

In 2022, when the museum upgraded its exhibitions, Jiang independently wrote the exhibition outline for the bamboo and wooden slip-themed display, striving to make it both academically rigorous and accessible to general audiences.

Over the years, he has been invited to deliver lectures at several universities, sharing the latest research findings on bamboo and wooden slips unearthed in Jingzhou with enthusiastic young students.

On June 14 this year, he participated in an online livestream session on bamboo and wooden slip restoration jointly hosted by the Jingzhou Museum and the Jingzhou Culture Relics Protection Center.

"We hope to pass on bamboo and wooden slip culture in ways that appeal to young people and bring ancient characters to life," Jiang said.

Photos

Related Stories

- Exhibition featuring ancient Egypt civilization closes at Shanghai Museum

- 9.18 Historical Museum docent dedicated to preserve the history

- People visit Inner Mongolia Museum in Hohhot

- Exhibition showcasing works by Russian painter kicks off at National Museum in Beijing

- Han-Wei Luoyang Ancient City Site Museum in Henan opens to public

Copyright © 2025 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.