Whitewashed atrocities: Japan tampers with textbooks, manufacturing 'collective historical amnesia'

Editor's Note:

Eighty years ago, the Japanese Emperor read the Imperial Rescript of the Termination of the War, announcing Japan's unconditional surrender to the allied forces in the World Anti-Fascist War. Yet 80 years later, when Global Times reporters conducted in-depth interviews in Tokyo and Nagano, Japan, they discovered a serious gap in the younger generation's understanding of Japan's modern history of aggression.

At the Iida City Peace Memorial Museum in Nagano Prefecture, which permanently exhibits evidence of Unit 731's human experiments, nearby students studying in the self-study area were unaware of its existence; young visitors to the infamous Yasukuni Shrine treat it as an ordinary shrine, oblivious to its ties to Japan's war of aggression... This collective historical amnesia stems from the systematic distortion and downplaying of Japan's history of aggression in its textbooks. However, Global Times reporters also observed that a significant portion of Japanese young cohort is eager to learn the truth and shows genuine interest in understanding history.

Yoko Kojiya, secretary-general of the Children and Textbooks Japan Network 21, a non-governmental organization, displays various versions of Japanese history textbooks to Global Times reporters on July 2, 2025. Photo: Xu Keyue/GT

The Iida City Peace Memorial Museum in Nagano Prefecture, Japan, is located on the third floor of the Iida Community Center and permanently exhibits evidence related to Unit 731's human experiments in China. The center is open to the public free of charge every day, so it is often crowded with office workers and students. However, during random interviews, Global Times reporters found that not only had none of these Japanese citizens ever visited the memorial museum in the same building, but some were completely unaware of its existence.

"I didn't know there was a peace memorial hall next to the study area," a male Japanese student preparing for exams told the Global Times. He came to study five times a week and has "learned a little about the history of the Sino-Japanese War online," but since it's not a part of the exam content, he has little interest in it. A Japanese female student said, "I come here to study almost every day, but I have never been to the memorial museum right next door, and I don't know anything about Unit 731's history."

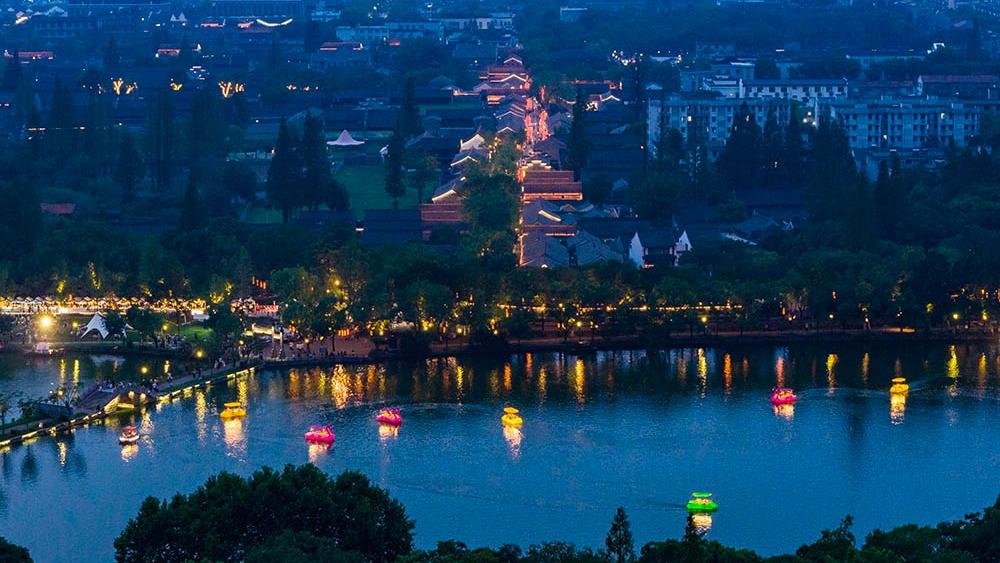

In early July, Global Times reporters visited the notorious Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo's Chiyoda ward. Under the shade of trees, students were seen chatting in small groups while drinking beverages, and office workers were taking short breaks. Some approached the shrine to bow and "pay respects to the spirits of the dead." Junichi Hasegawa, president of the Tokyo War Memorial Walkers and former Shinjuku ward council member, told the Global Times, "Young Japanese today have no idea what Yasukuni Shrine really represents - they think it's just an ordinary shrine. This is because history isn't properly taught in textbooks."

During the interviews, a veteran Japanese journalist told the Global Times that his daughter, born in the 1980s, considers the 9/11 attacks to be "war" - a war against terrorists - while historical issues between China and Japan are seen as "things of the past." His daughter, now a reporter for a major Japanese media outlet, represents Japan's elite class.

Yoko Kojiya, secretary-general of the Children and Textbooks Japan Network 21, a non-governmental organization, gave an example in an interview with the Global Times: "If you ask Japanese children, 'Which country did Japan lose to on August 15, 1945?' the answer will most likely be 'the US.' Almost no child would mention China."

Kojiya retired eight years ago after decades of teaching history in middle school. "Japanese children have a very poor understanding of the war between Japan and China," she said. "For instance, many don't know about the July 7 Incident (where Japanese troops attacked Chinese forces at Lugou Bridge, also known as Marco Polo Bridge, on July 7, 1937) or the September 18 Incident. When they hear 'war,' most think of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and believe that was the start of the war."

How do mainstream Japanese textbooks describe Nanjing Massacre?

Taking the Nanjing Massacre as an example, Global Times reporters compared the different descriptions of wartime facts in textbooks from several major Japanese publishers.

Yamakawa Shuppansha: "In December 1937, (the Japanese military) occupied Nanjing, the capital of the Nationalist government." Footnote: During this period, Japanese troops repeatedly engaged in looting, violence, and killed many prisoners of war and civilians (including women) (Nanjing Incident).

Teikoku-Shoin: "(The Japanese military) occupied Nanjing. In Nanjing, not only soldiers but also many civilians were killed (Nanjing Incident)." Footnote: This incident was condemned internationally, but the Japanese public remained unaware until the war ended. The full picture, including the death toll, continues to be investigated and studied.

Nihon Bunkyo Shuppan: "(The Japanese military) expanded its front and, after occupying the capital Nanjing in December, killed not only prisoners of war but also numerous residents (Nanjing Incident)." Footnote: At the time, this incident was not disclosed to the Japanese public. After the war, investigative materials were submitted during trials, and subsequent research uncovered various accounts of killings recorded in unit and soldiers' diaries. However, questions remain regarding the extent of unreported killings and how to assess the overall situation, requiring further study.

Tokyo Shoseki: "In late 1937, (the Japanese military) occupied the capital Nanjing, and in the process, killed many Chinese, including civilians such as women and children, as well as prisoners of war (Nanjing Incident)." Footnote: This incident is also referred to as the Nanjing Massacre. While various investigations and studies have been conducted on the number of victims, it remains undetermined to this day.

Global Times reporters noticed that, aside from Tokyo Shoseki mentioning the Nanjing Massacre in a footnote, all other textbooks used the term "Nanjing Incident." When referring to the death toll, they employed phrases such as "many," "various accounts exist," "still under investigation," and "undetermined."

"2014 was a critical turning point - the year the National Curriculum Standards and Textbook Authorization were revised," Kojiya told the Global Times. Under these standards, textbooks must state that "no consensus has been reached" when presenting figures or details in modern history that "have differing interpretations," and must avoid language that "might mislead children or students." Since then, nearly all textbooks have omitted any specific death toll from the Nanjing Massacre, Kojiya said.

From 'left vs right struggles' to 'rightward shift'

Japan's attempts to distort history have continued unabated since the postwar era. In 1965, a middle school history textbook authored by late Japanese historian Saburo Ienaga, then a professor at the Tokyo University of Education, was ordered by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology to delete or modify passages documenting historical facts such as the Nanjing Massacre, the atrocities of Unit 731, and the "comfort women" system, on grounds of "excessive descriptions." Ienaga argued this violated constitutional guarantees of educational and free speech rights, subsequently filing a lawsuit. This legal battle lasted 32 years (1965-1997), becoming postwar Japan's most influential struggle over historical recognition.

In 1982, the Japanese government decided to replace the term "aggression" describing Imperial Japanese Army's actions in China with "shinshutsu [advance in English]" in textbooks.

"I was absolutely shocked!" recalled Kojiya. "I had just become a middle school teacher that year when this major incident occurred. 'Shinshutsu' simply means 'going in and out,' whereas what the Japanese military did in China and elsewhere was clearly 'aggression.' Changing it to 'shinshutsu' was blatant fact-concealment. Utterly absurd!" Young Kojiya joined fellow teachers in criticizing the government's actions, while the Chinese government lodged solemn representations.

Junichi Hasegawa, president of the Tokyo War Memorial Walkers and former Shinjuku ward council member, tells Global Times reporters at infamous Yasukuni Shrine that young Japanese today are unaware of the notorious history behind this shrine, on July 3, 2025. Photo: Xu Keyue/GT

Beginning in the 1990s, Japan saw the emergence of groups attacking what they called "masochistic view of history," arguing that documenting past aggressions in textbooks constituted "self-flagellation" - that is, self-denigration that would deprive children of pride as Japanese. These groups established the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform in 1997 and began producing textbooks that not only completely omitted historical facts like the Nanjing Massacre and Unit 731, but actively distorted history and glorified acts of aggression.

Kojiya observed that from this point onward, Japan's textbook historiography entered a period of comprehensive regression. Having participated in civic textbook compilation since 1982, Kojiya has witnessed firsthand the ebb and flow of historical revisions in Japanese textbooks over decades. She noted that reviewing these past 80 years reveals an initial phase of "left-wing versus right-wing contention," but current textbook content has clearly shifted rightward.

Japanese youth yearn to know historical truth

What problems arise from being unable to learn the truth about history? When answering this question from the Global Times, Kojiya responded firmly: "Japanese youth will fail to grasp the gravity of war."

In July 2014, Japan's cabinet officially approved the reinterpretation of collective self-defense rights. At the time, Kojiya was still teaching middle school history. That day, a boy in her class asked: "Teacher, what are collective self-defense rights? Does it mean we'll have to go to war?" Soon, the whole class was abuzz with discussion. Kojiya recalled: "I was already in my 50s then, so one boy said, 'Teachers are fine - they won't have to fight.' Another added, 'The teachers won't, but we might.'"

Hearing this, Kojiya immediately corrected them: "No. If war breaks out, everyone - men, women, young, and old - will be dragged into it." She then showed the students historical materials and explained the atrocities committed by the Japanese military in China and elsewhere during the war. She told them: "War is far more horrific than you imagine. It strips people of their humanity. Even a gentle father or brother at home can become a soldier capable of unspeakable cruelty."

Junichi Hasegawa, now 88, has visited the Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders three times to kneel in apology. His father was once a member of the Japanese invasion forces in China. Hasegawa told the Global Times, "Schools must teach the truth of history. Every time I visit the Nanjing Massacre memorial hall, I see young Chinese actively learning about history. Yet in Japan, right-wing forces deny the massacre ever happened. It's tragic how our youth are misled!"

Near Waseda University, a prestigious Japanese institution, stands the Women's Active Museum on War and Peace (WAM) - Japan's first museum dedicated to documenting the Japanese military's wartime sexual violence. There, Global Times met Taiga Asano, a first-year University of Tokyo student visiting the museum.

Asano told the Global Times, "I knew nothing about 'comfort women' - not even that such a history existed - because it was never taught in school." He said he stumbled upon news of Japan-South Korea negotiations on the issue and felt compelled to educate himself. The 18-year-old added, "As young people, we genuinely want to understand historical truth."

Katsutoshi Takegami, a descendant of a member of Unit 1644 (a Japanese germ warfare unit in China), shared an anecdote with the Global Times: He once accompanied former Unit 731 teenage soldier Hideo Shimizu to speak at a Japanese middle school. Takegami recalled, "I thought we'd leave after his talk, but students asked 20 to 30 questions… Before that dialogue, I'd never realized how eager Japanese students are to learn the truth!"

During the interview with the Global Times, Kojiya stated, "Eighty years have passed since the war ended - those born postwar are now 80 themselves. It's time to create textbooks that allow children to learn accurate history together. Without knowing history, they can't truly understand Japan's domestic issues or today's complex global landscape."

"Despite attacks [from right-wing forces], there are still those fighting to preserve historical memory," she said.

Photos

Related Stories

- China slams U.S. for "whitewashing" Japan's WWII war crimes

- Chinese FM urges Japan to face history squarely to earn respect

- Exhibition on CPC's crucial role in war against Japanese aggression opens

- Japanese PM sends offering to notorious war-linked Yasukuni Shrine amid protest

- Japanese PM express "remorse" over WWII as 80th anniversary of defeat marked

Copyright © 2025 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.